Owl & Flowers Quarterly Review: January-March 2021

If you’ve been with this blog from the start you’ll know that my first post, a look back at some of my favourite books from 2020, was, shall we say, quite long. Some might say “daunting”, others might say “thorough”, I’ll just say long. To avoid this happening again in nine months’ time, it was suggested to me that I might like to give a quarterly review, as it were, of my top reads from the past couple of months, and so, here we are. This way I’ll hopefully get to highlight more great writing in a more accessible form, and it’ll also shed some light on my reading habits and maybe some underlying themes or concerns I’ve been ruminating on, or that the publishing world has decided to throw up. It also seems apt right now, with bookshops on the verge of finally reopening in England, to take stock of what I’ve read while I’ve been off, and what I’m excited to share with readers once I’m back.

Needless to say, it’s been a strange few months, and if you’ve read my previous posts you’ll already have some idea of the books I’ve been leaning towards. January was January, February was terrible for my reading, but in March I managed to step it up quite considerably, so a lot of the books I want to write about here are very fresh in my mind. I’ve also tried to lean away from talking about books I’ve already featured in blog posts before: for example, Eve Babitz would definitely have made this list had I not already covered Slow Days, Fast Company in my discussion on escapist reading. Some of these books have also been reviewed on my Instagram page, but I felt I could give them another airing here. And also, because it’s my blog and I can do what I like with it, I’ve grouped the books into rough categories, some pairings more surprising than others. I think the majority of these novels have been published this year, with just a couple of exceptions.

My Cat Yugoslavia and Asylum Road

It was pure coincidence that I read these two novels with so much in common so close together, but I’m very glad I did. I knew very little about the Balkan conflicts before reading, and I still don’t know much, but I’m so grateful for what these two very different but complementary writers have shared. The ignorance of people like me is something the protagonists of Statovci and Sudjic’s novels come up against constantly through both books: no one around them can understand why they behave the way they do, and they find it impossible to talk about the reasons. My Cat Yugoslavia has more space for magical realism than Asylum Road, but I was struck how both books use very concrete symbolism to discuss the narrators’ mental states, how both characters seem to feel more comfortable talking in metaphors, how those metaphors bleed into reality — sometimes to allow for healing, sometimes to create danger. In My Cat Yugoslavia, the main character Bekim is strangled by the pressures of masculinity, but struggles to voice this, so allows himself to be periodically literally strangled by a pet boa constrictor he buys in the first chapter, as well as entering into an abusive relationship with an anthropomorphised cat: Bekim’s relationship with the cat develops in tandem with chapters written from the perspective of his mother, Emine, as she details her engagement and marriage to Bekim’s father, who starts off charming but soon becomes abusive, violent, and even, after their move to Finland, a criminal. Instinctively you want to draw lines between symbols and their psychological meaning (snake = masculinity, etc) but it’s never that simple, and the meanings shift constantly — at times, the snake is frightened, cautious, a comforting presence; sometimes the cat is greedy and violent, sometimes gentle and supportive, sometimes a man in cat’s clothing, sometimes literally just a cat.

Both books centre on young characters who grew up in Yugoslavia, and moved to the UK (in Asylum Road) and Finland (in My Cat Yugoslavia) after the breakout of war. Anya, Sudjic’s protagonist, and Bekim, Statovci’s, both grow up attempting to come to terms with their own trauma as well as that of their parents, all while living in societies hostile to immigrants and surrounded by people who seem unable to view them as having suffered any kind of trauma in the first place. Anya lies to her fiancé, Luke, about having an allergy to certain soft fruits — in reality, she can’t eat them because for her they evoke memories of living under siege in Sarajevo, of eating only from food parcels, of the texture of flesh. And yet, the main thing Anya and Luke have in common, it seems, is a shared love of true crime podcasts. Tunnels and roads are recurring images throughout Asylum Road, the title itself gesturing to Anya’s status as a refugee while also literally referring to the road of that name in Peckham, south London, and the fact that much of the novel takes place on the road or in transit, despite Anya not knowing how to drive herself. Anya is looking for a route out of her insecurity and fear — she wants a road to stability and sees that in Luke, particularly after her proposes to her early in the book; she can never let herself be, because she has never had that freedom. She’s always trying to get somewhere, that somewhere being largely defined as away from where she was before. Both Bekim and Anya, in running away from their deeply traumatic childhoods, end up travelling back home again, with differing outcomes in each case. Each journey home is laden with symbolism, and with terror; each one prompts growth, but Bekim and Anya find very different ways to grow and change.

Creatively Writing the MFA: Bunny and A Swim in a Pond in the Rain

If George Saunders’ exquisite exploration of seven Russian short stories, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the Platonic ideal of the Creative Writing MFA experience, then Mona Awad’s Bunny is the dark, disturbing, flipside of that coin. I’m not going to pretend these books have much in common other than the MFA setting itself, but I think it’s interesting to look at how two very different writers in very different mediums portray the same academic environment — one that I also have some familiarity with, albeit in the UK rather than the USA.

Saunders’ book is probably going to end up being the best thing I read all year. It is wonderful, full of awe and kindness, generosity and love for humankind. Who knew an anthology of stories with accompanying critical essays could contain so much warmth? (This is coming from someone who unapologetically loves reading lit crit too.) My friend Connor described the book as being like walking through a model village with George as your guide: that is exactly the vibe, gentle guidance, gesturing to tiny details that once you’ve seen them, you can never forget. Saunders feels like the ultimate teacher, with so much patience, quiet authority, life experience to draw on, and a seemingly endless capacity to keep learning. His models for writing short stories mirror a lot of my feelings from my own Creative Writing MA: writing fiction (or in my case, poetry) is starting a conversation with a reader, and there are certain conventions of being considerate that need to be adhered to on both sides in order for a story to be successful. Writers need to earn the trust of a reader before taking them off the rails; readers need to go in with a good faith approach and an openness to where the writer wants to lead them. Ultimately the sense you get from A Swim in a Pond in the Rain is that all stories are in some way a form of play, by which I mean they are a space where we can explore and experiment and tug at the rules that bound the world we live in. That’s not to say there are no rules to stories though — fun is only fun if it has boundaries, choices, and limits. There’s no one better to teach this than George.

On the other hand, Mona Awad’s brilliant thriller, Bunny, is a sharp, satirical look at the darker side of the MFA. The narrator, Samantha, is constantly hitting a brick wall when it comes to connecting with her workshop group and her supervisor, and as someone who studied Creative Writing, Awad’s mocking of the language of the academy was particularly entertaining for me.

I record the number 1098 in my notebook. Which is the number of times I’ve heard “the Body” mentioned since being at Warren. Because at Warren, the Body is all the rage. As though everyone in the academic world has just now discovered that they are vesseled in precarious, fastly decaying houses of bone and flesh and my god, what material. What a wealth of themes and plot! I still don’t quite understand what it means to write about The Body with title caps but I always nod like I do. Oh yes, The Body, of course.

Other words I’ve been keeping track of: space, gesture, and perform.

I don’t want to give away too many spoilers about Bunny, but let’s just say that it turns out that Samantha’s classmates — called the Bunnies, as they all refer to each other as “Bunny” — are writing “The Body” in myriad ways, some more literal and terrifying than others. Samantha succumbs to their near-suffocating version of intellectual femininity, and is drawn into their world of cocktails, cutesy dresses, and salon evenings. Bunny teeters on the edge of the irritating “not like other girls” trope but does manage to save itself from leaning too far into that, I feel, all the while exploring the violence, both outward and inward, of female desire and the stifling nature of the MFA. Samantha’s tutors consider themselves to be mavericks, but they perpetuate the same tropes we’ve seen a million times before, praising writing that mimics their own, expecting too much from students, lacking an awareness of their own privilege. Bunny is ultimately tremendous fun, a thrillingly dark page-turner, and a wild, psychedelic ride.

Mothering Instincts: No One is Talking About This and Detransition, Baby

I read these two books a couple of weeks ago, one after the other, and they are both brilliant, but boy did I take an emotional beating. Patricia Lockwood and Torrey Peters have both been longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction this year, alongside some other really incredible writers whose novels I can’t wait to read. These were the main two I’d already been excited for before the longlist announcement, but I’m also desperate to get my hands on the new Yaa Gyasi and How the One Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones, and I’ve heard amazing things about Raven Leilani’s Luster. If you saw my 2020 round-up you’ll know also how much I love Ali Smith and what I thought of Summer — this might be best saved for another post entirely but it makes me sad to see her consistently getting onto longlists and never making it to the prize for her recent novels. Almost like the Seasons should be judged as a whole rather than as four distinct books, or like she should be awarded some kind of award that takes into account her whole career, rather than just these individual novels — but that’s just my opinion.

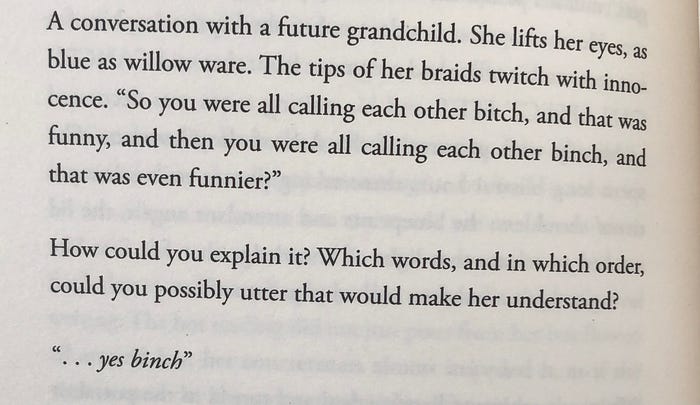

Anyway, enough of the general Women’s Prize talk, onto Patricia Lockwood. Lockwood was originally known as a poet and essayist, and her memoir Priestdaddy was a real breakout hit; she’s also made a name for herself online, with several viral tweets, often involving her cat, Miette. No One is Talking About This is her first novel, and many reviewers have claimed it to be the first novel to talk about and portray Being Online in an authentic and relatable (as opposed to cringe) way — it’s touched a nerve with many people, myself included, to have our infinite scrolling habits exposed so clearly. The first half of the novel is a frantic dive into the exhilaration that comes from the internet, ways of living and feeling alive inside what Lockwood refers to as “the portal”, how this virtual life can feel like everything. The mind has a life online while the body feels trapped, unhappy, and unsatisfactory in the real world. The second half of the novel draws on a real crisis Lockwood’s family experienced and demonstrates starkly how some things that happen are so far removed from this online life, even if you think you’re inextricably enmeshed in it. Lockwood is such a funny and tone-sensitive writer, she knows exactly how to set up jokes and pull the rug out from under the reader, as well as when to return to comic imagery at the worst moment for the most jarring effect. The book is genius, Lockwood is genius, and it’s rare for me to read something that feels so terrifyingly close to my own life and experiences. No matter how online you are, some things are too big to be allowed space there.

Meanwhile, Torrey Peters’ phenomenal debut novel, Detransition, Baby, poses a lot of similar questions to No One is Talking About This when it comes to concerns of modern femininity, family, and motherhood, but in starkly different ways. In her novel, Peters focusses on the relationships between three connected people: Reese, a trans woman, Ames, Reese’s ex who used to identify as a trans woman but has since detransitioned and is living as a man, and Katrina, Ames’ boss who finds herself, after a whirlwind affair, pregnant with Ames’ child. Ames finds the prospect of parenthood, and in particular being seen as a father, to be near unbearable without the right kind of support network, so he proposes to Katrina that Reese, who had always wanted to be a mother, should be involved in raising the baby. The novel then alternates between flashbacks of Amy (Ames’ previous name) and Reese’s relationship and counting down the weeks after the conception of Katrina’s baby. The structure is quite brilliant at allowing characters to be deeply flawed, make questionable decisions, then revealing information in later chapters that sheds new light on why they behaved that way. It’s an absolute masterclass in building relationships between the characters and the reader: by the end of the novel you understand perfectly why each person has done what they have done, and you are so familiar with them that it hurts to close the book. Peters has given us a deeply nuanced portrayal of queer life, obviously focussing heavily on the experience of trans women, which some readers might not be ready for yet. It’s discomforting and shocking at times, recognisable and warm at others, challenging and engaging all at once. At its core, it’s a novel about families, how we make families by listening to each other, and how “being a family” — and arguably “being in a relationship” — has little to do with common ground and is more concerned with looking in the same direction, heading towards the same goal. Reese and Katrina both want to be mothers but have different reservations about what that means; Ames doesn’t want to be a mother, but can’t face filling the traditional “father” role either; as a mixed-race woman and a trans woman respectively, Katrina and Reese both experience different but possibly parallel obstacles in their lives, and negotiating around those is hard for both of them.

Peters talks openly about the connections between femininity, sex, and shame, about the issues with referring to people in their thirties as “queer elders”, and about the surprising things people have in common versus the equally surprising ways we are divided. Peters dedicates Detransition, Baby to “divorced cis women” — if that surprises you, she’s talked in interviews about the difficulty of finding people to relate to when transitioning as an adult, as many older trans women had dealt with different struggles to what she saw for herself. Divorced cis women, on the other hand, had similar experiences: they had envisioned a life for themselves, but that idea of their future had been irrevocably shattered, and they’d had to start over again. This narrative felt closer to Peters’ sense of how transitioning would change her life, and she found solace and comfort in the ways these women had re-established themselves. It’s a beautiful sentiment and the strength, compassion, and openness of those divorced women is present in the novel in the form of Katrina, who is 39 and divorced her husband following a miscarriage. Becoming pregnant again is as shattering to her world view in lots of ways as the idea of being a “father” is to Ames. You don’t have to be a trans woman to relate to Reese’s tendency to self-sabotage, for example, but of course there are parts of her story that are uniquely trans, and are out of your reach if you’re a reader who isn’t. The point is, you might relate to more than you expect but you won’t relate perfectly to everything: some things will be beyond you. But that’s ok — just like in life, you can still share space with that, it’s ok, and arguably it’s important to do so.

Small Press Spotlight: Astral Season, Beastly Season

I thought it might be a nice idea in each of these quarterly roundups to take a moment to talk about an independent publisher I’ve been particularly delighted with over the past few months. For this first instalment, I want to talk about a book I finished literally two days ago from a fantastic small press I only recently heard about. The book is Astral Season, Beastly Season, the debut novel from Japanese poet Tahi Saihate, translated by Kalau Almony, and published by Honford Star. The press started off publishing classic East Asian literature, but have since opened up their list to contemporary writing too.

Astral Season, Beastly Season is a story of two halves, centred around Morishita and Yamashiro, two high school boys who find out that their favourite J-pop idol is going to be arrested for murder. In order to save her from prison, the pair embark on a plan to frame themselves for the crime, changing the course of their lives forever. The first part of the novel is narrated by Yamashiro, who becomes embroiled in Morishita’s plot to convince the police of his own guilt, while in the second the story is picked up years after these events by another of their classmates, who reflects on the two boys she knew and how the crime reverberated around her community. It’s a deceptively slim book that packs in a lot of philosophical concerns: a repeated refrain through the book is that “at the age of seventeen, you either become a star or a beast”, as one of the characters read once in an English lesson, though the terms “star” and “beast” refuse to be pinned down at any point, twisting and shifting through a variety of literal and symbolic meanings. It’s about alienation, the lengths people will go to for connections, the ways in which we value (or undervalue) our lives. I was moved, disturbed, and shaken by this strange and daring novella.

I also wanted to mention quickly how beautifully made this book is. As a physical object, it’s lovely. There’s nothing particularly special about it as such, but the care Honford Press have clearly taken over the production shouldn’t be ignored: the paper stock is beautiful, the endpapers feel lovely, the cover design is perfect — striking, disturbing, delightful — and the typesetting honestly makes the physical act of reading the book such a joy. Despite only running to 125 pages, Astral Season, Beastly Season feels (I mean literally) satisfyingly weighty. It’s substantial, it feels good to hold, good to slip into your bag. Maybe this sounds silly to some readers but as someone who has to consider not only personal taste but how to merchandise and make books seem visually appealing, I do think it’s important to make something as nice as this.

So not only is Astral Season, Beastly Season a fascinating philosophical exploration of humanity, generosity, friendship, being a teenager, and celebrity, it’s also introduced me to a new independent publisher to love. As soon as I’m back at work I’ll be ordering Tower and Cursed Bunny for sure, and possibly the entire back catalogue as soon as my bank account will allow it.