Foxes & Their Tales

Last Friday, we had a visitation. Like many people in London, we’ve been well aware of our local fox thanks to the haunting wails we hear almost every night, but we’d only spied him once — until last week. He was fast asleep, curled up in our garden, possibly for the whole afternoon, though we only got to watch for about half an hour before he woke up, performed some leisurely stretches, and wandered off. It felt magical to see a wild creature so close, and so nonchalant: dogs were barking in other gardens, he slept right though, and we’re pretty sure he spotted us through the glass doors. ‘Tis the season for foxes to breed, after all, so it’s no surprise that lots of people are reporting closer encounters with them than usual, but why does it feel quite so enchanting?

What is it about foxes that we find so compelling? They’re so very nearly dogs, but also entirely not. For city dwellers, they’re basically charismatic megafauna, so estranged are we from the natural world. There’s also something very charming about them: we admire their mischievous nature, their bushy tails, their adaptability, their refusal to leave urbanised spaces. (I’m sure if I kept chickens I would feel quite differently.) Foxes have played an important part in our mythic lexicon for centuries: in many cultures, foxes are portrayed as tricksters, as in Aesop’s fables and the Reynard cycle, and in Japanese folklore foxes can shapeshift into humans, and in various tales use this ability for good and ill. In Native American mythology, Coyote performs a similar role as a divine trickster, in some stories helping create and introduce evil into the world, in others bringing fire to human beings for the first time. Closer to home, the fox has always fascinated the British: a collection of Reynard stories was one of the first books printed by William Caxton, and fox fables form a not insignificant part of foundational British literature. Chaucer reworked a traditional Reynard story for ‘The Nun’s Priest’s Tale’ in The Canterbury Tales. Robert Henryson, the great Scottish makar, wrote his Morall Fabilis around 100 years later and filled it with Reynardian material, drawing directly from Chaucer for ‘The Taill of Schir Chanticleir and the Foxe’ and toying with reader expectations of the fable form and the familiar animal archetypes he was working with. Since then, foxes have continued to abound in Western literature, with modern presentations as varied as Disney’s Robin Hood, the infamous “Crack Fox” from The Mighty Boosh, and the symbolic fox in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag to name but a few.

It’s safe to say that every culture with a native species akin to a fox has been anthropomorphising that fox for quite some time, and when I looked at our garden fox in North West London, I couldn’t help but see him surrounded by all that literary baggage. As Jenny Diski puts it in What I Don’t Know About Animals,

“Creation myths, cave art, fables, allegory, all take animals and shape them to our own ends as if they were made of plasticine or dreams. In some sense they are: the natural world and everything in it that isn’t us, are aspects of our mind. They are taken in by our senses and become our understanding of what is outside ourselves. But nothing we observe and think about is entirely outside ourselves.”

Does it matter that we project so much onto our local fox? He doesn’t know or care — or maybe he does, who am I to assume what happens in his head? — but does it make a difference to how we look at him? It’s hard to know how we would perceive the fox without all this, because we can’t. Some would say these narratives make us too compassionate towards the fox, who is, after all, a scavenging predator, violent towards other animals we consider cute, like cats, or animals we consider useful, like chickens. But we’re the ones who have brought those creatures onto the fox’s territory, created arbitrary lines between what land is ours and what is his, and in the case of cats, introduced a new non-native predator into his environment. Is it not, perhaps, partly our guilt that makes us look at the fox with warmth in our eyes?

Anyway, enough anthropology, it’s time to give you what you came for: a listicle of my Top 5 Fox Books.

Fox 8 by George Saunders

If I want to convince someone to read Fox 8, I just make them look at the opening lines:

“Deer Reeder:

First may I say, sorry for any werds I spel rong. Because I am a fox! So don’t rite or spel perfect. But here is how I lerned to rite and spel as gud as I do!”

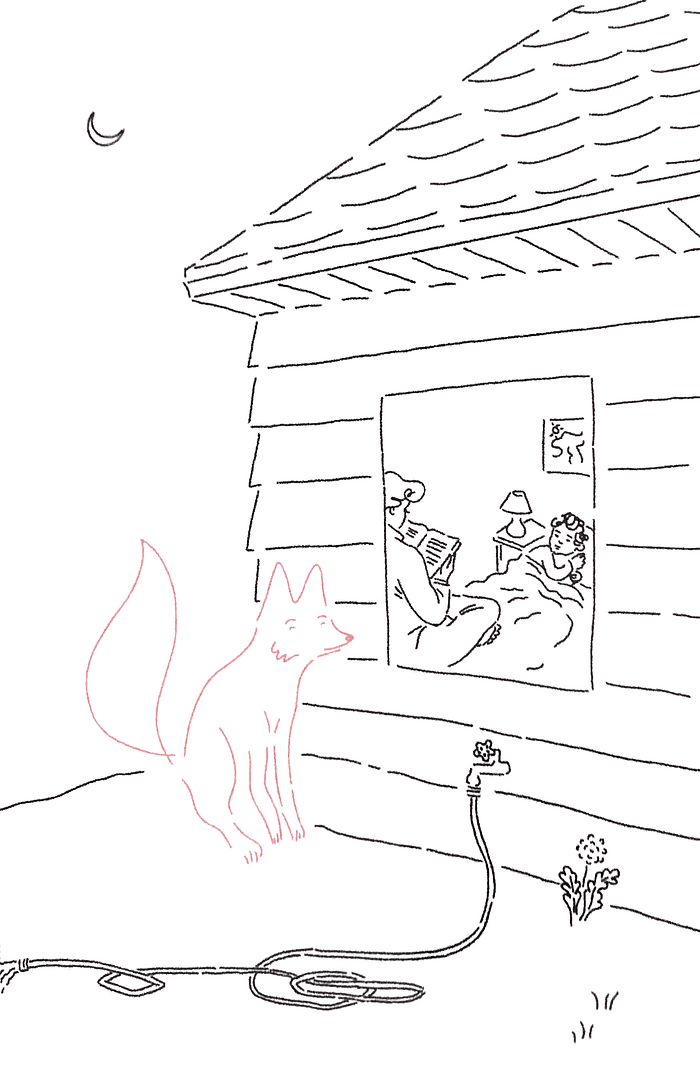

In true, traditional fable style Fox 8 focusses on whether humans can live alongside the natural world, or whether we will always tend towards exploiting it even when we claim to care for it. The eponymous Fox 8 tells the story of how he learnt to speak and read English by listening through a window to a child’s bedtime stories. A sweet premise, but underneath that this is a story about violence and failures of kindness and empathy. “The sweet tone leads you to believe that the author is going to protect the innocent fox, because he made him,” says Saunders in an interview for the Guardian. “And then, as is the case in the real word, the most innocent person is just as susceptible to violence as the least.”

Fox 8 feels Seussian as well as classically Saunders-esque: it’s playful, funny and entertaining while also being serious and brutal. And like all good fables, it ends with a moral, as told by Fox 8 to the “Yumans”: “If you want your Storys to end happy, try being niser.”

Dead Astronauts by Jeff Vandermeer

When I reviewed Dead Astronauts on my instagram page, I talked a lot about the very admirable ways it tries to take hierarchy out of storytelling, and take the human out of the idea of consciousness or narrative voice. This, obviously, makes it a difficult read — that’s ok, books are allowed to be difficult — and not one you’re likely to be able to “solve”. Dead Astronauts is a prequel of sorts to Vandermeer’s Borne, exploring, among other things, the origin of the three disintegrating bodies in bleached white containment suits (thus dubbed astronauts) that serve as a recurring motif in Borne. There’s also, holding the many narrative threads if not together, then at least sort of in the same dimension, a blue fox, the result of many brutal experiments by the Company, who seems to play the role of both prophet, guide, and trickster depending on who’s listening.

“You want. Things to be words. That are not words. Could never be words. Your fox is some other construct. We did not agree to that. We do not call ourselves foxes. A thing you created that is not me. To think an autopsy was a person. To think a dissection meant a type of mind. If I went rummaging through your carcass, would I find you?”

The fox’s portion of the book is a horrifying read: experimented on over and over by Charlie X on behalf of the Company, the fox repeats what it has been subjected to, killed and brought back to life to be tortured again, its body simply a resource for science. It’s just an animal, after all. The fox again, as in Fox 8, becomes an agent for talking about how humans relate to and interact with nature, though Vandermeer’s vision has less room for optimism: we are violent, we exploit the world around us, we twist it until it becomes entirely unsustainable, and although we are tormented by what we do we cannot stop and we do not repent, not really, because we will just do it again, and worse. Through the various characters in Dead Astronauts, and pointedly through the voice of the fox, Vandermeer forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that we are the perpetrators of climate violence, and we do it in the name of science, or progress. We do it because we think of ourselves as outside the system, when we are really, really not.

The Blue Fox by Sjón (trans. Victoria Cribb)

“Blue foxes are so curiously like stones that it is a matter for wonder. When they lie beside them in winter there is no hope of telling them apart from the rocks themselves; indeed, they’re far trickier than white foxes, which always cast a shadow or look yellow against the snow.”

Another blue fox, another weird ecological fable. The Blue Fox, set in rural Iceland in the late 1800s, splits into two main narratives: one is the story of Abba, a woman with Down’s Syndrome who has been cruelly abandoned by her family because of her condition. She is taken in by a young bohemian called Fridrik, who is the only person in her life to treat her with humanity and empathy. Abba and Fridrik’s story is cut together with that of Baldur Skuggason, a priest turned hunter, who is tracking a mysterious blue vixen. As the book hurtles towards its wild, almost Lynchian conclusion, you get caught up in the music of it, watching the prose dance through the pages, images recurring like themes from a song. The foxiest part of the book is the final section, which I don’t want to spoil: suffice to say, it’s really something.

In a brilliant interview for The White Review, Sjón discusses the importance of myth in the modern world, particularly following an event like 9/11, where it was hard to face the reality of what we saw through news broadcasts: “Somehow the unreal took over. It had a massive effect on a very deep level on our understanding of what is real. That’s why I think the myths are coming back, because they exist in that field of human experience, where the real and the unreal simply exist together, and in a way you can only explain the real through what is supposed to be unreal…In times where grand narratives are needed we look to the grand narratives of our culture.” Is it surprising then, at home in the UK, that a resurgence in British folk horror has come at the same time as the troubling resurgence of British nationalism? Is this how we combat the unreality of Brexit narratives, with reminders that this land we are meant to love is harsh, haunted, and harrowing, and no matter how much we say we control it, borders are really just arbitrary human constructs? Sjón’s fox somehow says all of this and more.

The Sandman: The Dream Hunters by Neil Gaiman & Yoshitaka Amano

One of Neil Gaiman’s many Sandman spin-off stories, but markedly superior to most of the others, The Dream Hunters is an enchanting dive into Japanese folkloric traditions surrounding the figure of the fox, or kitsune. Gaiman originally posed this story as a retelling of a traditional tale he had discovered while writing the English screenplay of Studio Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke, but it soon transpired that he wrote the whole thing from scratch, demonstrating, as if we needed further proof, his unparalleled ability to tap into exactly what makes a culture’s mythos tick. In The Dream Hunters, Gaiman weaves his own creations from the Sandman universe into the tale of a fox and a monk who fall in love, illustrated by Yoshitaka Amano, whose blend of traditional Japanese drawing with art-nouveau styles is the perfect medium for a Sandman tale. The monk is cursed by a local scholar to fall into a neverending sleep; the fox takes his place; the monk must descend into the world of the Dreaming to appeal to Morpheus (in his guise as the King of All Night’s Dreaming) to put things right. The monk sacrifices himself to let his beloved fox go free, and she in turn takes revenge on the scholar who caused the enchantment in the first place. So far, so fairy tale. What makes Gaiman’s fox so powerful is her tenacity, her determination, and the contrast between her tenderness for the monk and her belief in the importance of revenge. When dying, the monk implores her to look to the ways of Buddha rather than vengeance, but in her conversation with Morpheus — who appears to her as a giant black fox — she says she will make things even first, then turn her attentions to a good life. Many Sandman stories go this way: the “moral”, “correct” ending will be visible to the characters, but they choose the more fallible, human, understandable option instead. At the end of the story, Dream’s raven asks him ‘“But what good did it do?”’ — Dream’s inscrutable answer, as always, is that “Lessons were learned”. Matthew, the raven, has another question, (which really should be asked at the end of every Sandman fable): ‘“And did you also learn a lesson?”’

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

How could we complete this very minor summary of foxes in modern literature without including The Little Prince? In Saint-Exupéry’s fable, the fox arrives at a moment when the prince feels himself to be most insignificant: he has arrived on Earth and is beginning to understand how small his own planet is in comparison; he has seen rosebushes, and also understands that his rose back home was lying when she said she was one of a kind. Despairing at his own smallness in the universe, he cries. That’s when the fox appears, and he begs it to play with him, to be a salve for his loneliness, but the fox declines — sort of. To play together, the prince must first tame the fox. Rather than the typical connotations of mastery and control that go with the idea of taming, the fox simply describes it as “establishing ties”, showing the prince that even though the fox is just one of many foxes, and the prince is just one of many boys, through the act of taming, or forming a bond, they become to each other “unique in all the world”. This brings pleasure — the fox talks about feeling happy in the hours preceding the prince’s visits, and how the colour of the wheat fields, which are of no importance to him as a fox, bring joy as they remind him of the prince’s hair — but it also brings pain: there is heartache as the prince prepares to depart, and, when the fox says, ‘“You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed”’, we can’t help but feel that the prince’s urgency to return to his planet and his rose is somewhat neglecting the responsibility he now has to the fox. In teaching the Prince the importance of establishing ties, the fox opened himself up to the pains of having those ties broken. ‘“It has done you no good at all!”’ the Prince declares.

“It has done me good,” said the fox, “because of the colour of the wheat fields.”

Saint-Exupéry wrote in letters about taming and raising a fennec fox he found while working as an airmail pilot in the Sahara: he was clearly very familiar with the animal’s behaviour and had a great tenderness for them. The fox is an important choice: it straddles a fragile line between the human world and the animal world, being so closely related to dogs, and yet so very different in the way it lives. The playfulness of foxes helps us project further characteristics onto them: they’re somewhere between dogs and cats, perhaps, mischievous, independent, aloof yet goofy. The beauty of the fox vignette in The Little Prince is not only its philosophy — no one is truly unique, it’s our bonds and the ways we connect to each other, the ways in which we see each other that make us unique to each other — but also its tactility. I defy anyone to read those passages and not want to play with the fox. Saint-Exupéry doesn’t describe the fox in any great detail, nor does he describe the taming process particularly (he simply says, “So the little prince tamed the fox” and leaves it at that), but still we have a beautiful sense of this fox, this one specific unique fox, as we read. To finish on a rather trite observation: is that what great literature is about? Taking something broad and universal and turning it into an experience “unique in all the world”, unique because it depends not just on what is being presented to us, but how we connect to it, the ties we establish with it, the eyes through which we see it? Is it about taming the reader? Do we, willingly, let ourselves be tamed?